Showing all 12 results

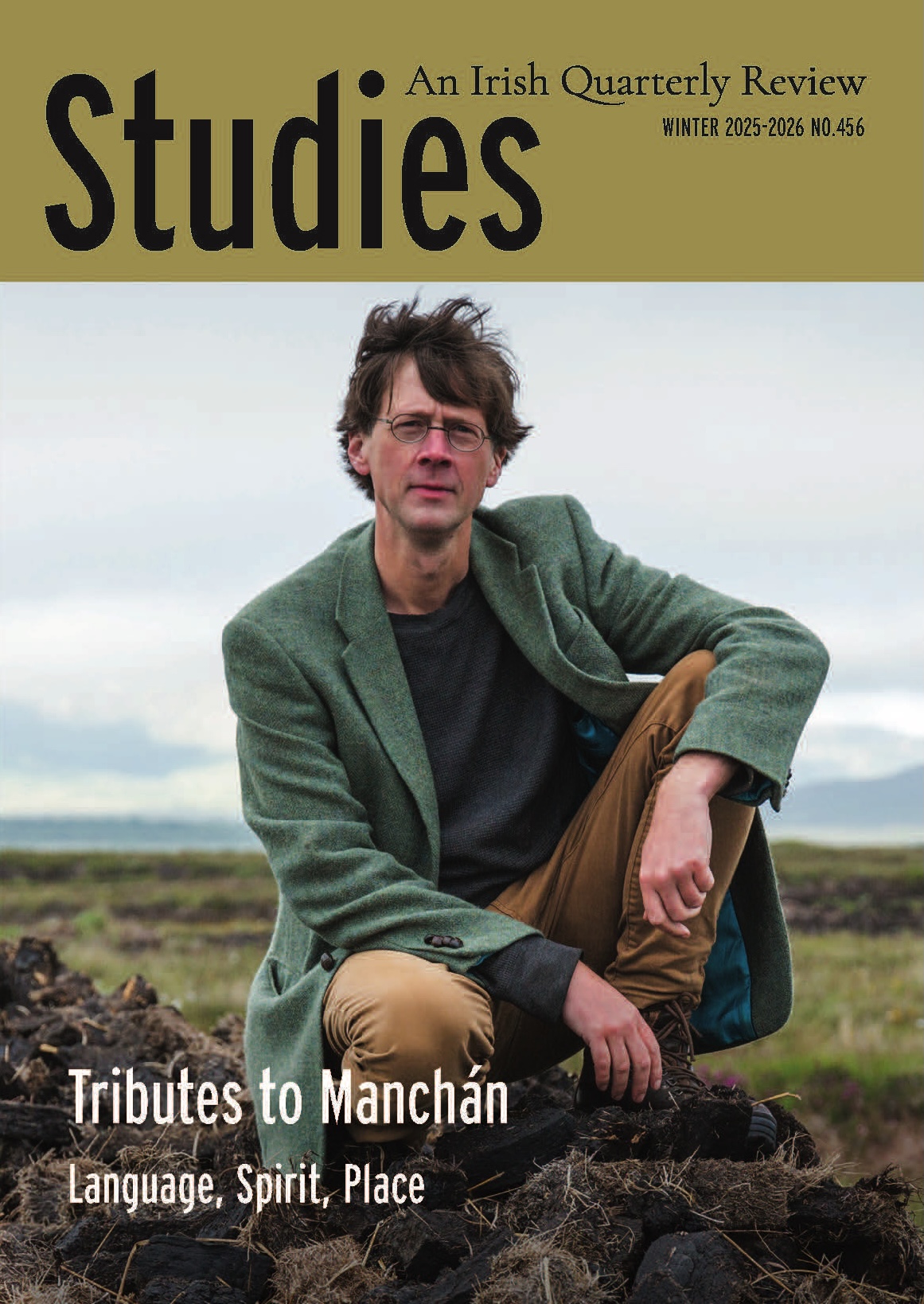

Tributes to Manchán: Language, Spirit, Place Winter 2025, Volume 114, No 456

Full Issue

€10.00+p&p

When the German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, still a student, travelled to Denmark to meet Niels Bohr in 1924, the two of them paid a visit to Kronborg Castle in Helsingør – the royal castle in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Heisenberg recalled Bohr’s remarks in his memoirs: Isn’t it strange how this castle changes as soon as one imagines that Hamlet lived here? As scientists we believe that a castle consists only of stones, and admire the way the architect put...

Read Editorial

When the German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, still a student, travelled to Denmark to meet Niels Bohr in 1924, the two of them paid a visit to Kronborg Castle in Helsingør – the royal castle in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Heisenberg recalled Bohr’s remarks in his memoirs:

Isn’t it strange how this castle changes as soon as one imagines

that Hamlet lived here? As scientists we believe that a castle

consists only of stones, and admire the way the architect put them

together. The stones, the green roof with its patina, the wood

carvings in the church, constitute the whole castle. None of this

should be changed by the fact that Hamlet lived here, and yet it is

changed completely. Suddenly the walls and the ramparts speak a

quite different language. The courtyard becomes an entire world,

a dark corner reminds us of the darkness in the human soul, we

hear Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’. Yet all we really know about

Hamlet is that his name appears in a thirteenth-century chronicle.

No one can prove that he really lived, let alone that he lived here.

But everyone knows the questions Shakespeare had him ask, the

human depth he was made to reveal, and so he, too, had to be

found a place on earth, here in Kronborg. And once we know that,

Kronborg becomes quite a different castle for us.

Bohr is hardly the only scientist to note the limitations of rational categories and scientific language in conveying the fuller meaning of phenomena; Einstein, Feynman, and even Dawkins come to mind. Yet it is not uncommon for scientists to be reductive – to regard a castle as really nothing more than the stones, roofs and furnishings that make it up; to view a landscape, for all the beauty we perceive in it, as merely a set of contiguous material forms: earth, water, rocks, plant life, and clouds, each with its own molecular makeup and all illuminated by photons. Whatever significance we find beyond these base elements, they may think, is of psychological interest indeed – as an expression, perhaps, of Freud’s ‘oceanic feeling’, that sense of being one with the external world – but it is not a significance that is in the things themselves. The world, on this view, consists only of brute ‘stuff’; any meaning it has is merely what we project onto it.

Meaning presupposes consciousness, of course, so in that limited sense the view is correct. And one can grant that the meaning a place acquires through experience or engagement or emotional attachment is, in a sense, projected onto it. That is what the humanistic geographer Yi-Fu Tuan has in mind when he writes that ‘undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value.’2 Yet Tuan also recognises the many layers of meaning that are disclosed rather than imposed. Even the physical aspects of a place – its objective form – may help to shape us and may even bear on what we cautiously call national character. Bohr hints as much when he tells Heisenberg that a Bavarian must find Denmark flat and boring, whereas to Danes ‘the sea is all-important. As we look across it, we think that part of infinity lies within our grasp.’ A people who inhabit maritime lowlands in the north develop, in imagination, social practice, mythology, and historical memory, a different sense of the world from those who have always lived among the mountains of a landlocked south. Myth, history, and communal experience all contribute to meanings that take root in memory and are, in a real sense, sedimented into the place itself.

In his 1977 lecture ‘The Sense of Place’,3 Seamus Heaney cherished the traditional Irish sense of landscape as ‘sacramental’ – ‘instinct with signs, implying a system of reality beyond the visible realities’. This vision of things might have been lost as nineteenth-century anthropology, ‘increasingly scientific and secular’, sought ‘to banish the mystery from the old faiths and standardise and anatomize the old places’. But the poets, from Yeats onwards, reinstated the old world, ‘more magical than materialistic’, providing a nourishment ‘which springs from knowing and belonging to a certain place and a certain mode of life’. It is not Heaney’s claim that this intimacy between people and the place where they are reared is a peculiarly Irish thing, but that it took on a certain urgency in Ireland on account of the deeply fraught questions of the ‘possession of the land and possession of different languages’.

Language is key. The indigenous language of a place carries a wealth of memories and meanings that an imposed language may never fully access, a truth which holds in the Irish case as much as anywhere else in the colonised world. For Manchán Magan, the Irish author, documentary maker, and broadcaster whom we commemorate in this issue of Studies, was a critical and inciting conviction. ‘An Ghaeilge’, he wrote in his hugely popular Thirty-Two Words for Field, is a complex and mysterious system of communication. It has encoded within it the accumulated knowledge of a people who have been living sustainably on these rocky, verdant Atlantic islands for millennia. As a result, it is profoundly ecological, with an innately indigenous understanding that prioritises nature and the land above all things.

For Manchán, the Irish language has a ‘hidden wisdom’, just like so many other old languages that evolved ‘before the strictures of reason and rationality were imposed upon society’.5 These indigenous languages preserved that special relationship to place that made them repositories of an ancient knowledge which is threatened with extinction by present-day technological sophistication.

The bond, then, between language and land is intimate. The language holds the means of articulating the wisdom, and the landscape acts as a kind of ‘mnemonic’ – it helps us, as Manchán puts it in Listen to the Land Speak, ‘remember things that are often greater than the landscape itself’. The geographical features, he adds ‘are vessels for the history, beliefs and culture of our people, going back thousands of years’.

At times Manchán wrote critically of Christianity’s contribution to the rupture between the Irish people and their land through its suppression of older systems of belief, but he acknowledged that Celtic Christianity also served to retain an intimate connection with the natural world through its unique form of ‘animistic Christianity’, one the monks then brought to Europe between the sixth and the ninth centuries:

These oddball missionaries who wrote poems about the beauty

of the blackbird’s call, or the whitethorn’s berries, or a midland

lake at dawn, became beacons of light for a culturally slaughtered

Europe. These were the likes of St Feargal from Co. Laois,

who went to Salzburg, or St Killian from Cavan, who went to

Würzburg, or the many other Irish monks who went to Italy and

France to bring light to the darkness.

Manchán Magan died on 2 October 2025. After just a few months of enduring an aggressive cancer, he was imithe, as his website now announces, ar shlí na fírinne. He was gone ‘on the path of truth’. The outpouring of tributes was remarkable. It was clear to everyone, as the Irish Times obituary put it, that ‘he was no ordinary media personality.’ He was ‘not given to ego or fashion’, it continued; ‘he was known for his open-hearted outlook, vast reserves of language learning and the practical application in his own life of ecological values.’ Thanks to his books, his film productions, and his infectious love of the Irish land and language, his legacy is secure.

***

Manchán’s funeral – or ‘liturgy of remembrance and farewell’ – was held on 6 October in the chapel at Gonzaga College, Dublin, his alma mater. Many people gathered to celebrate his life through story and song. One of those who spoke was Tom Casey SJ, who visited Manchán just days before he died, when he found him ‘frail, yes, but bríomhar fós, still full of life’. In “The Fifth Province: A Tribute to Manchán Magan’, an extended version of the words he spoke at the funeral, he presents Manchán as a prophet – ‘not one who foretells the future, but one who tells forth into our present, who speaks with the voice of the spirit into the silence of our forgetfulness’.

In ‘Influence in Transmission: Scéal an Deisceabail Teanga’, Liam Mac Amhlaigh concurs in thinking Manchán a ‘prophet’, but he proposes that he was also ‘a disciple of the language’. Manchán put the Irish language at the centre of his work, even when he travelled beyond the country’s shores, so he not only challenged Irish people to reflect on their own valuing of the language, but he also brought Irish into conversation with other minority cultures and indigenous communities throughout the world.

Nuala King recounts an exchange she had with Manchán regarding the Aboriginal Australian concept of Kanyini, a sacred principle of ‘caring and practicing responsibility for all beings and for the land that sustains them’. In ‘Holding the World Together: Myth, Language, and the Reawakening of Kanyini in the Irish Imagination’, she explores resonances between this concept and the’ deep ecological consciousness embedded in Irish myth and language’.

Siobhán McNamara ran the library and was Green Schools Coordinator in Gonzaga College for a number of years, and her work included bringing guest speakers to the school to address the students. In ‘Memories of Manchán’ she recalls Manchán’s occasional visits when he entertained his audience with stories from his travels, his projects, and his school days. True to form, he would speak in Irish, but he always made sure that he didn’t leave his listeners behind. What all the essays in this short series of tributes have in common is an affirmation of what McNamara thanks Manchán for at the end of her essay – his energy, sincerity, creativity, and eloquence.

***

Other essay contributions to this issue of Studies include Bryan Fanning’s ‘Immigrants, Diasporas and Faith-Based Welfare’. Fanning notes a pattern that has held in many places around the world whereby vulnerable migrant groups rely inordinately on informal community care, especially that provided by faith-based organisations. In ‘Literature as Theology: A French Paradox’,

Kevin Williams observes that, in spite of the official policy of laïcité in France, religion continues to have a prominent place in the country’s public culture and religious concepts are transmitted as a live cultural resource through literature. Is there a model for Ireland here?

In ‘The Impact of Demography and Migration on Employment in Ireland’, Martina Lawless and Tara McIndoe-Calder build on their chapter in the recently published fifteenth edition of The Economy of Ireland. They chart the shifts in the Irish population since the Great Famine, through both natural increase and swings in net migration, noting in particular that both inward and outward migration is driven by concerns over access to labour markets.

Carmel Gallagher reflects in ‘Life to the Full: The Experience of Returned Irish Missionaries’ on Ireland’s failure to value the work and experience of missionaries, whose contributions to the material development and to the pursuit of social justice in the Global South have given Ireland considerable ‘soft power’ in international relations.

James Kelly observes in ‘Roman Catholicism at a Crossroads’ that the Church today is experiencing the same rift between traditionalists and progressives that it did during the modernist crisis of the early twentieth century, a rift that has its origins in the increased rationalism and dogmatism of the institutional Church in the years after the Reformation and the Council of Trent. If the rising tide of internal discord and external decline is to be stemmed, he argues, the Church will have to be more open, inclusive, and dynamic.

In ‘Catholicism, Motherhood, and Intergenerational Agency in Elaine Feeney’s As You Were’, Kate Costello-Sullivan engages with Feeney’s 2020 novel about a group of women who find themselves in the same hospital ward, each of them victims of the state’s ‘architecture of containment’ and often the Catholic Church’s collusion with it.