Showing all 11 results

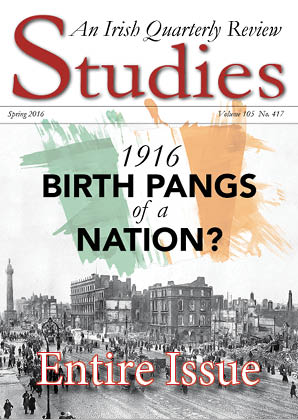

Editorial Studies enjoys the rare distinction, as an Irish periodical, of pre-existing the Easter Rising of 1916, whose centenary is now being commemorated. Founded in 1912, the summer issue of that year contained a poem by one of the future leaders of the rebellion, Joseph Mary Plunkett. In spring of the following year Pádraig Pearse’s essay, ‘Some aspects of Irish literature’, appeared, the text of a lecture he had delivered before the National Literary Society in Dublin a few months earlier. In 1916 itself, the journal, operating under the constraints of British censorship, had to eschew direct political commentary on what had just happened. Apart from two pieces by architects on ‘the reconstruction of O’Connell Street’, ‘one of the noblest streets in Europe’, as one of the pieces put it, half of which, owing to ‘the unhappy events of Easter week’, ‘now lies in ruins’, the editor had to content himself with more oblique allusion in the form of essays on three ‘Poets of the Insurrection’, Thomas McDonagh, Pearse and Plunkett. In what the essay on MacDonagh calls ‘the lightning-charged atmosphere, which still hangs around their names’, as the writer explained, there can be ‘but incidental reference to the facts of their careers’. But their status as patriotic heroes, within a mere month of their executions, is already being suggested. In 1966, public celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising was uncomplicatedly triumphalistic. Future Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald, then a member of the Seanad, while admiring the courage of the 1916 leaders, struck a more critical note in Studies with reference to the political and social philosophy enshrined in the Proclamation and the veneration in which this had been, in his view, for too long held. But he did not otherwise criticise the leaders themselves. This was left to Fr Francis Shaw SJ in a long essay, ‘The canon of Irish history – a challenge’, held back until 1972, two years after its author’s death, having been judged too hot to publish in 1966. Unsurprisingly, his reassessment of the hitherto more or less unquestioningly sainted Pearse still, unsurprisingly, produced controversy when it appeared, partly reworked, six years after publication of the anniversary edition for which it had been intended. ‘Even today’, as John Swift writes in his review of Roy Foster’s Vivid Faces in these pages, ‘for a substantial number of Irish citizens, it is not politically acceptable to question the ethics or wisdom of the 1916 leaders’. The essay and the controversy have since been lucidly placed in context by Dáire Keogh in the centenary edition of Studies itself in 2011. Despite some criticisms, Professor Keogh felt able to call it ‘the most prescient essay’ in the journal’s hundred years of existence. Three years later, historian Patrick Maume subjected the Shaw essay to telling scrutiny but conceded that what he had said about it ‘does not mean that [Fr Shaw] was not on to something’. This is more widely acknowledged now, of course, and thinking about 1916 has moved on. The essay itself has remained the single most sought-after reprint from Studies in the decades since it first appeared. Studies, it might therefore be said, has ‘form’ when it comes to commemorating 1916, and the ghost of Frank Shaw and his revisionism hovers over it as the current issue appears. The challenge, clearly, is to avoid the temptation of judging the past with the benefit of later knowledge. ‘The period around 1916 is too far away for most of us to comprehend intuitively its mind-sets and dynamics’, as John Swift writes in the review just mentioned, ‘but near enough – and familiar enough from school learning and casual reading – to allow us the easy assumption that we know it well’. Those early decades of the twentieth century in Ireland and Britain, interpreted against the background of a world war engulfing Europe between 1914 and 1918, were strangely complex. But if the passage of time means that all kinds of familiarity recede before us, comprehension of the wider issues at stake and the long-term implications of particular steps and mis-steps and steps not taken may grow. Thus we may admire unstintingly the bravery of those who led the Rising and not least their dignity in facing death, while reserving the right to question rigorously the mandate on which they acted and the wisdom of what they did, judged by its outcomes in the immediate and longer term, some of them at least all too foreseeable even then. Séamus Murphy dedicates his robust, provocative piece, ‘Dark Liturgy – Bloody Praxis’, to the memory of his older Jesuit colleague Fr Shaw and readers familiar with ‘The canon of Irish history’ will recognise the provenance of Dr Murphy’s thinking. His focus is partly on Pearse’s deployment of the notion of blood-sacrifice and the pseudo-religious language deployed in the process. The language, he avers, was not so much blasphemous as idolatrous, in effect inculcating worship and appeasement of a false god. ‘It might masquerade in Catholic devotional dress, but its meaning, the master whom it served, was not the Christian God’. This is not a new criticism, but it is pursued here with unusual theological rigour and the implications of Pearse’s language are carefully spelt out. Séamus Murphy is no less concerned with the ways in which Pearse’s philosophy and the thinking expressed in the Proclamation are essentially anti-democratic and do violence to Christian, and specifically Catholic, social thought. For him, the Rising’s social praxis is ‘destructive and dehumanizing’. In consequence, ‘democratic transubstantiation of the Rising never succeeds’ and, he believes, it never can. ‘Irish governments’, as he writes, ‘repress the IRA but avoid rejecting the Rising’, while insisting that it ‘must be “reclaimed from the men of violence”’. But this is an impossible task: ‘separated from its leaders’ intentions and worldview, ‘the Rising has no meaning’. By acting as they did, the leaders ‘perpetrated a spiritual violence on the Irish nationalist community from which it has not fully recovered’. The problems created by canonising the violent events of 1916 as pivotal in the emergence of the modern Irish state have become ever more obvious with the passage of time. How, then, should we, as a nation and as a state, commemorate those events – and the whole period – now? This is the subject of Stephen Collins’ essay in these pages and, for the political editor of the Irish Times, ‘Fr Shaw’s views have as much relevance today as they had in 1966, because the underlying reality has not changed. A warped view of what happened in 1916 is still having a malign influence a century later’. It was ‘the decision of a minority within a minority of the Irish Volunteers’. What was their mandate? How can we criticise the murder of Constable Ronan Kerr of the PSNI by republican dissidents in Omagh 2011, if we do not also condemn that of Constable James O’Brien of the DMP by the rebels in Dublin in 1916? The huge importance of the Rising is not to be denied. But it ‘has been taken out of context and elevated into the supreme founding event of the modern Irish state when, in fact, it was one event in a series between 1912 and 1923 that changed the political structure of the country’. This kind of distortion is a central concern of Dr Sylvie Kleinman’s enlightening discussion of how America and France in particular celebrated the centenaries of their revolutions, which she presents as a context within which to consider what Ireland should and should not be doing now. She criticises the influence of ‘the great age of epic narrative and historical mythologising, the 19th century and its “invention of traditions”’ on those celebrations, giving rise to ‘the popular concept of heroic destinies and heroes who faced self-sacrifice to achieve them’. This is a ‘cumbersome legacy’ for Ireland in 2016. As elsewhere, certain events and certain individuals become mythologised, others, arguably of no less significance in the nation’s development, get ignored. And so, as others here point out and as former Taoiseach John Bruton does not tire of insisting, the likes of John Redmond, in particular, and the tradition of constitutional politics gets written out of the national script. When the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising was being celebrated in 1966, Éamon de Valera, sole surviving commandant, was entering his second term as President of Ireland and Fianna Fáíl, the anti-Treaty political party he had led since the Troubles until assuming the presidency, was in power. The celebrations at that time were undoubtedly coloured by those circumstances. Professor Ronan Fanning, author of the magisterial Fatal Path. British Government and Irish Revolution 1910–1922 (2013) and now of an acclaimed biography of de Valera, provides a fascinating picture of the early stages of his subject’s ascent, his ‘apotheosis’, to become the dominant figure in Irish politics during some forty years. If he lived to know of Fr Shaw’s article in Studies in 1972 (he himself died at a great age three years later), Mr de Valera will understandably have given it little credence. As he told the Sinn Féin convention in October 1917, ‘I regard my election here as a monument to the brave dead, and I believe that this is proof that they were right, that what they fought for – the complete and absolute freedom and separation from England – was the pious wish of every Irish heart’. The advance towards an independent republic, and his own emergence as its prospective leader, was retrospective validation of the Rising. That view continued to prevail in many quarters in 1966, and still does. Ronan Fanning notes how, in his election campaign in East Clare, de Valera, who wore his Volunteer uniform, carefully cultivated the Church, broadening his appeal ‘by inviting parish priests to preside at his election meetings’. The Rising had confronted the Catholic bishops with a crisis, constraining them between the obligation to condemn secret societies like the IRB and political violence, from whatever source, on the one hand, and the need to stay as close as they might to their priests and their flock, on the other. Dr Oliver Rafferty’s intriguing essay traces their uncertainties and divisions as they tried to respond to the crisis unfolding around them. In a private note in October 1916, which he may have intended to form part of a statement from the bishops as a group, Bishop Patrick O’Donnell of Raphoe, the future cardinal, wrote, as might have been expected, that rebellion against ‘constituted authority’ was a crime, ‘unless the people as a whole consider their grievances to be intolerable and beyond hope of pacific redress’. (This was clearly not then the case). Striking the kind of balance that became more difficult later on, he added that, although the nation would not forget those who had died in Easter week out of devotion to Ireland, ‘neither will she forget the multitude of her sons who shed their blood so freely in Gallipoli and France “to die for Ireland”’. Revealing some of the mixed feelings people like himself nurtured in such conflicted times, he went on to say that, although obedience to proper authority was indeed a duty before God, nevertheless the ‘Administration which suffered [and by this he clearly meant “allowed”, “permitted”] the Curragh Mutiny’ and nursed rebellion North and South ‘had no right to execute the rebels of its own manufacture’. But the time for balance was passing. Essays in this issue by J Anthony Gaughan and Mairéad Carew respectively, treat of two other important figures from the period. Fr Gaughan writes on Alfred O’Rahilly, who, as still a Jesuit scholastic when Studies was founded, helped with its management and contributed a wide variety of articles and book reviews to the earliest issues. Having left the order in May 1914, he became what might be described as close to but not quite central in the events of the time. He was a tireless Sinn Féin propagandist during the revolutionary years, but opposed de Valera at the time of the Treaty. He later worked with him in government, as he also did with other parties, forthright and bravely principled throughout his long career. The importance of Eoin MacNeill, Frank Shaw’s mentor and friend and another significant contributor to Studies, needs no elaboration. A key, partly tragic figure in the events of 1916 (as Fr Shaw and others would say, owing to the duplicity of Pearse), Dr Carew stresses his role in the vital work of cultural revitalisation in later years, a contribution which, like that of the Gaelic League, in which he played such a prominent part, is easily overshadowed and forgotten by a narrowly militaristic narrative of events. Professor Thomas O’Grady’s essay on his grandfather’s service on the Somme during the First World War is a salutary reminder of larger events happening elsewhere and points to what 1916 may tend to bring primarily to mind for not a few of our Northern fellow-countrymen, as well as the ways in which – to quote the words of John Horne, whom he cites – ‘Our island’s conflicting memories of the war still blur the retrospective view and prevent us from taking the war’s full measure’, in South and North alike. This, happily, is now at last beginning to change. John Swift’s review of Roy Foster’s much praised volume of ‘personalised history’, Vivid Faces, has already been referred to. Swift’s thoughtful, essaylength review is of great value for its own sake as a complement to the other contributions on the Rising and related matters in the present issue of Studies. A similar comment applies to Judge Dónal O’Donnell’s review of Professor Osborough’s history of the UCD Law Faculty, which becomes the vehicle of a very long, but unusually valuable study of judicial practice and thinking at the highest levels in Ireland from the early years onwards, as the new state evolved towards maturity. Among many others who were prominent in the process, mention might be made of Arthur Clery, one of the very early professors in UCD, who, as Judge O’Donnell writes, ‘took a brave and important role in the War of Independence by becoming a Dáil Court Judge’. We are at present enduring something of an avalanche of books and essays and programmes of all kinds connected with 1916 and it shows no sign of abating. Remembering and honouring are both important, but in as inclusive a way as possible. And there are also judgments to be made about what the cataclysmic events of a hundred years ago have to teach us about our present and for our future. The poetry of Yeats tends to be much quoted in relation to the Rising and the events around it. Some other lines of his, not generally drawn on in this connection, taken from his great poem Among School Children, come to mind: What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap… Would think her son, did she but see that shape With sixty or more winters on its head, A compensation for the pang of his birth, Or the uncertainty of his setting forth? Yeats, of course, was referring to himself. But, one hundred years after that ‘pang of birth’ in 1916, what are we to think of revolution’s child? Was what happened worth it? Is it ‘compensation’ enough? Does the prosperity of those ‘children of the nation’ who have managed to stay and thrive at home compensate for the too many who have had to leave, our very own economic migrants, over the decades? Does the success and growing prosperity of some make up for all those others who stayed but could not thrive in a society growing even now increasingly more unequal? What are we to make of all the violence and brutality and loss of life – all the Constable O’Briens and Constable Kerrs, all the nameless ‘collateral damage’ (that demeaning phrase!) like the humble carter James Stephens saw in St Stephen’s Green, shot dead when he tried to retrieve the cart stolen from him by the Citizen Army to construct their barricade, taking first his livelihood and then his poor life itself? And so many others, murdered, maimed, traumatised, orphaned, bereaved? What are we to say of the often futile adversarialism of our skewed politics? What of our divided country? What of the scandal of homelessness, a crisis which Fr Peter McVerry, who has been campaigning tirelessly on the issue for some fifty years, says makes a mockery of our celebrations? What of the often embarrassed disowning of our Christian heritage (the Church’s own sometimes egregious failures notwithstanding), the lazy lapsation into vague secularism, the dumbing of spirit and the coarsening of soul, which the 1916 leaders would find strange indeed? Ireland has, in truth, achieved much in a hundred years and, in some ways, could even be said to have led the world. Parnell’s ‘march of a nation’, however enabled, has come a long way. But we also have very much to ponder at a moment like this. Stephen Collins ends his thoughtful piece on what 1916 means to us now by regretting ‘that the decade of commemoration taken, as a whole, does not appear to have encouraged the open minded and honest examination of the past that could feed into a more balanced view of the present’. It is not too late. Cover caption: Sackville Street (O’Connell Street) As Seen From One Of The Houses On The West Side © Collection of T W Murphy at dublincitypubliclibraries.com